Australia is shirking its responsibility to protect refugees, again. This time, Cambodia, one of Asia’s poorest countries, is in the process of signing an agreement to resettle Australian-bound asylum seekers.

In a move that has been condemned by activist and human rights groups, it is expected that Cambodia will offer permanent resettlement to people seeking asylum from war and persecution. Details of the agreement are yet to be released, but late Tuesday night the Secretary of State, Ouch Borith confirmed the agreement, stating that his government would “do the work according to international standards”.

So what is so wrong with this agreement? Isn’t it good that desperate people who are seeking safety will finally have access to the constantly evasive legal protection?

The thing with refugee resettlement, is that countries that offer resettlement are required to provide education and labour opportunities, not simply safety. As Phil Robertson, deputy director Human Rights Watch in Asia says, Cambodia’s “capacity to take care of asylum seekers or refugees is low”.

The kingdom of Cambodia is still recovering from its own history of civil war and violence. It was only a few decades ago that scores of people fled the nation as it was consumed in brutal violence, genocide and war crimes under the Khmer Rouge regime. With one of the worst human rights records in the region the nation is still recovering. Many Cambodians live in abject poverty, surviving hand to mouth while children and women are vulnerable to exploitation and trafficking. Australia is consistent donor to the nation, providing more than $244.5 million in aid over the past three years.

The kingdom of Cambodia is still recovering from its own history of civil war and violence. It was only a few decades ago that scores of people fled the nation as it was consumed in brutal violence, genocide and war crimes under the Khmer Rouge regime. With one of the worst human rights records in the region the nation is still recovering. Many Cambodians live in abject poverty, surviving hand to mouth while children and women are vulnerable to exploitation and trafficking. Australia is consistent donor to the nation, providing more than $244.5 million in aid over the past three years.

Human rights lawyer, David Manne told ABC radio that “there are real concerns about people’s safety [in Cambodia]. Beyond that, there are indeed other obligations that Australia has committed to at the international community in relation to refugees”, including a commitment not to move refugees around the world to precarious situations where their safety could not be guaranteed.

The Human Development Index in 2013 ranks Cambodia at 138 out of 187 countries. And guess where Australia sits? Second. In case you didn’t get that, I’ll repeat. Second. Meanwhile the two other countries Australia has shirked its responsibility of protecting asylum seekers to, Papua New Guinea and Nauru, sit at 156 and 164 respectively.

Considering asylum seekers are currently living without basic human rights in Australian run offshore processing centres in the aforementioned Nauru and PNG, perhaps the Cambodia agreement is a positive step forward for those who are found to be refugees.

But the answer to these issues should not come down to an either or.

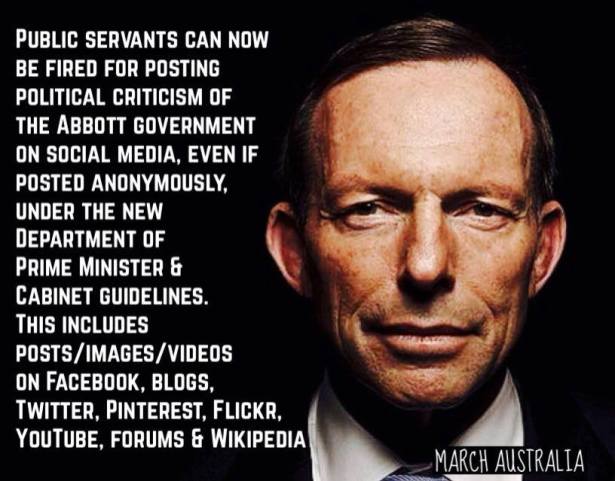

Australia has an obligation, not just to humanity, but to an international convention it helped to draft, to provide protection for people fleeing war and persecution.

I have worked with people who have come to Australia by boat, both those living in Australia and those in the offshore centres. Not one of these people I have met took a boat journey because they wanted better economic opportunities. They came because they cannot live in their homeland. They feared for their lives. That journey across the ocean on a small boat is not a choice. They are aware of the very real reality of death and those who do make it, often begin to grow grey hair, a physical sign of the internal stress they experienced during the week long journey. But rather than Australia recognising the bravery and acknowledging our commitments of the convention, they are treated to a hostile reception and tossed between political policies like a pig-skin on a football field.

met took a boat journey because they wanted better economic opportunities. They came because they cannot live in their homeland. They feared for their lives. That journey across the ocean on a small boat is not a choice. They are aware of the very real reality of death and those who do make it, often begin to grow grey hair, a physical sign of the internal stress they experienced during the week long journey. But rather than Australia recognising the bravery and acknowledging our commitments of the convention, they are treated to a hostile reception and tossed between political policies like a pig-skin on a football field.

Phil Robertson describes the Cambodia agreement as “absolutely shameful and [deserving of] public condemnation across the region, from Phnom Pen to Canberra and by the UNHCR”.

Only time will tell what the response to this agreement will be, but if history is any indicator, it will somehow slip through legislation, just as the Offshore Solution did in 2012.

All of these policies serve one explicit (political) purpose; to stop people dying at sea. The means should never justify the end, particularly when we are discussing the lives of the most vulnerable people in the world and a nation still developing.

We can do better Australia, can’t we?